In Praise of Conservatism, In Hopes for Its Future, and Why the Wisconsin Union-Busting Law is Wrong Anyway (2011)

Originally published as a Facebook Note March 13, 2011.

|

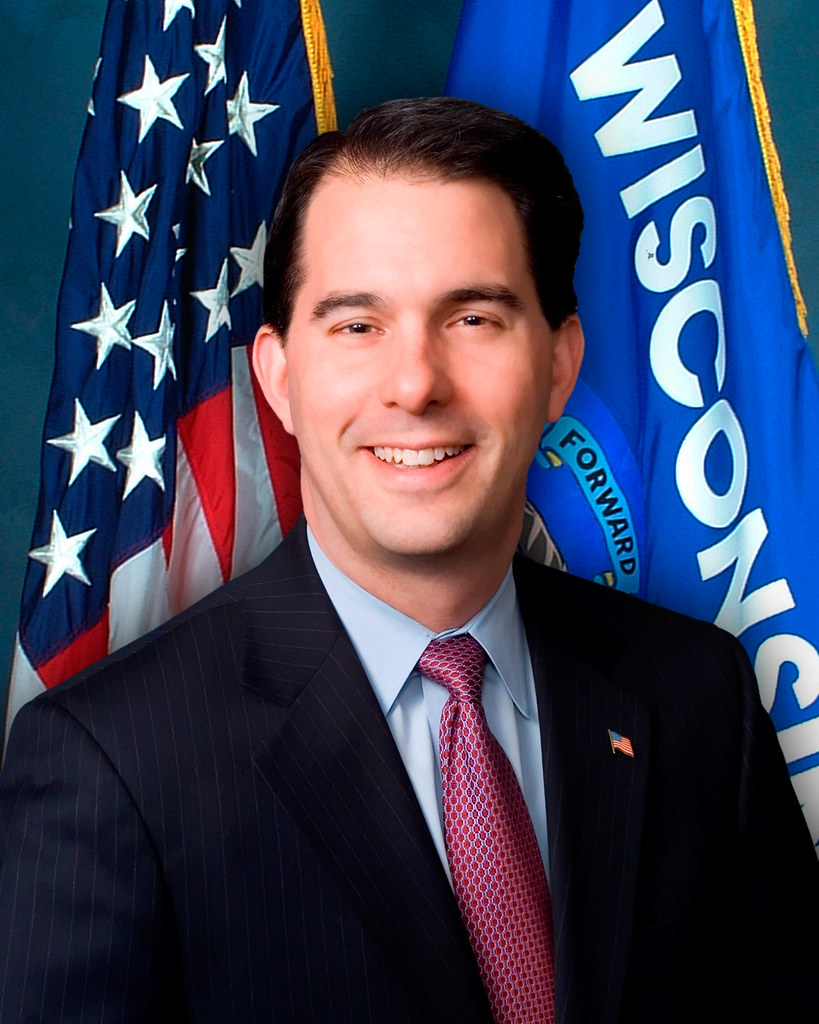

| Scott Walker, Governor of Wisconsin (2011-2019) |

(In which our author, having spilled an obscene amount of words on other people's sites, decides to mess up his own page instead.)

I grew up in the 1960s, in a conservative house in a conservative town in a liberal era. When I was growing up, conservatism stood for small, efficient, clean, government, and a cautious approach to social change. Even so, there was room in the conservative idea for public goods. The civil rights, environmental, consumer protection and campaign finance legislation that passed during the late 1960s and early 1970s passed with conservative input and support.

In serving as a counterweight to the era's liberal zeitgeist, conservatism was at its best, and made distinctive contributions to American political and social life. It reflected skepticism about government activity and spending, reminding us constantly that we couldn't regulate or spend every problem out of existence. It stood for traditional American values, stating as the ur-conservative, Edmund Burke, did that societies contain accumulated wisdom that it is dangerous to overhaul with radical change, even or maybe especially when change is well-intentioned. It provided a voice for the private sector, for the businesses and industries that are the engines of the American economy. And, perhaps most important, it provided limits on the ability of liberalism to work its will. "Checks and balances, Jefferson," proclaimed John Adams long ago, in a letter arguing against religious establishment on the grounds that any group of people would oppress others given the opportunity, and concluding, "Human nature, know thyself!" Conservatism provided the necessary checks to balance liberalism.

Some time in the 1980s, conservatism moved from being the counterculture to being the zeitgeist itself. Perhaps, as Alan Wolfe has suggested, that led to a concern for power over ideas. I think it's just difficult to adjust to having responsibility for government and for formulating policy programs.

Whatever the reason, conservatism has lost the moral and intellectual mooring it had in previous generations. Far too much of what passes for conservatism these days is political appeals based on fear and loathing of others, and a smug rejection of any information that challenges their rigid doctrine. Examples abound: the "Hell no!" strategy of congressional Republicans in 2009-10; the variety of bizarre rumors surrounding President Obama; and the anti-intellectual approach to accumulated data and experience on topics from climate change tp the recession to economic inequality to government in general. Some programs surely waste money, but some programs produce social benefits far beyond their costs, and surely even rock-ribbed conservatives know this, but it's easier and flashier to say "Investment is just a Democrat (sic) word for spending."

State budgets are in a mess, to be sure. There's plenty of blame to go around. The budget-cutting strategy of our Iowa Republicans, however, seems more oriented to sticking it to groups they don't like rather than actually saving money. Besides going after teachers' unions and public employees' unions under the guise of budget savings, the governor's measure targets family planning programs, public broadcasting, anti-smoking programs, railroads, preschools and even sabbatical leaves for professors at state universities. The savings from the last one are microscopic, but it sounds good, at least to those who think sabbaticals are paid vacations.

Conservative appeals today are based on fear and or loathing of unpopular groups. Around the country, there are bills to bust public employee unions, repeal gay marriage laws, and target immigrants, as well as congressional hearings this week on the menace lurking in Muslim mosques from undercover terrorists. This bilious pattern is based on no principle, but inflames suspicions, fans prejudices, and makes us less of one nation.

To, finally, the Wisconsin bill. This is not a positive example of functional government. It is an ugly, divisive political power play. Union-busting, in Wisconsin and the states like Iowa that hope to emulate it, achieves no public purpose. (The education budget savings in Wisconsin had already been agreed to, and were passed in a separate bill.) It targets a group, blaming them unfairly for state budget woes that were brought on by a collapsing economy and exacerbated by reckless tax cuts. Perhaps non-union members can be inspired to support this cause. (Perhaps not, from early public opinion polls.) More disturbingly,breaking a well-resourced Democratic-leaning interest group fits a pattern of extraordinary Republican efforts in the past decade to rig the system in their favor: denying black votes in Florida in 2000, recalling the governor of California in 2003, Texas's mid-decade redistricting, the Citizens United decision, and now this.

To participate constructively in the American political process, as they have for decades past, conservatives need to develop a vision for America, one based on achievement of ideals, not on narrow self-interest and sticking it to groups they don't like. Ronald Reagan had a vision in the 1980s, albeit a nostalgic one based on a misremembered past. Today's conservatives can't even claim that much.

They need to do another thing, too, which is to recognize that unchecked conservatism can't achieve everything society needs. It can make us more private. It can make us more armed. But it can't make the world more beautiful, unify the American people, provide public spaces and public goods, empower those who need opportunity, or secure the public from the occasional abuse of private power. For a lot of that government can help. And unions too.

Comments

Post a Comment